Apr. 23. 2020

Twitter has been taunting us: When he was in quarantine from the plague, William Shakespeare wrote “King Lear.”

He had an advantage, of sorts: Shakespeare’s life was marked by plague. Just weeks after his baptism at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford – upon – Avon in 1564, the register read, “Hic incepit pestis” (Here begins the plague). Shakespeare, the son of the town’s glover, survived it and many further outbreaks. Much of his work was composed, if not in lockdown, then in the shadow of a highly infectious disease without a known cure.

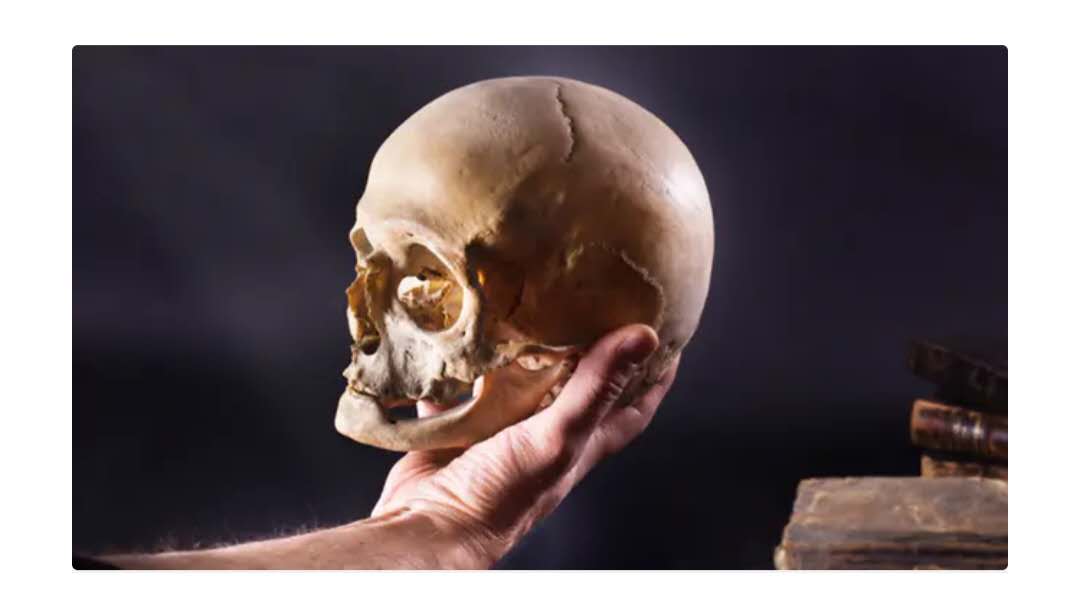

Man and woman, to be sure, die in any number of inventive ways in Shakespeare’s plays. In “Othello,” Desdemona is smothered in her bed. John of Gaunt dies of old age exacerbated by the absence of his exiled son in “Richard II.” In “Hamlet,” Ophelia drowns. But no one in Shakespeare’s plays dies of the plague.

Rene Girard, the French critic, wrote in a famous essay that “the distinctiveness of the plague is that it ultimately destroys all forms of distinctiveness.” Plague was indifferent to the boundaries erected by society, and its appetite was ravenous. Thousands of husbands, wives and children were led to the grave.

Shakespeare’s response to plague is not to deny mortality but rather to emphasize people’s unique and inerasable difference. Elaborate plots, motives, interactions and obscurities focus our attention on human beings. No one in Shakespeare’s plays dies quickly and obscurely. Rather, last words are given full hearing, epitaphs are soberly delivered, bodies taken offstage respectfully.

Shakespeare is not interested in the statistics – what in his time were called the bills of mortality. Maybe, like Shakespeare, we should focus not on statistics but on the wonderfully, weirdly, cussedly, irredeemably individual.